Linda Pang has a penchant for the old. A vice-president at CPG Consultants, she has worked on a number of key architecture conservation projects that have helped to form Singapore’s identity.

These include the Old Hill Street Police Station, the new extension block of the Central Fire Station, and the National Gallery project.

In her spare time, she volunteers as part of the Singapore Memory Project, which aims to capture and document precious moments and memories related to Singapore.

d+a caught up with her to find out how the challenges and motivations of her job.

If you were to give Singapore a report card on its architecture conservation efforts, what would it say?

I’d give Singapore an “A”. A significant amount of effort and resources has been invested into the conservation of politically and historically significant buildings, which is especially commendable considering the ever-increasing demand for land and space.

Aside from government initiatives, there are also many passionate people who involve themselves in conservation efforts, and it is inspiring to see the lengths to which they go to help preserve the buildings and spaces which they feel are important to Singapore’s culture and history.

Why is architecture conservation so important to a country’s identity and social fabric? What more do you feel it can do to ensure it makes progress in this direction?

In our modern society, the pace of change can be extremely quick, and our urban landscape is no exception to this. I believe that societies learn and grow best when we truly appreciate our past and the myriad lessons it provides. Physical buildings and spaces offer powerful testimonies to our history, allowing us to develop shared and collective memories as a community, and give us the chance to have vivid walks down memory lane.

For example, Pearl Bank Apartments is an architectural masterpiece by our own local architect, Tan Cheng Siong. The horse-shoe-shaped residential building contains split-level apartments and offers amazing spatial experiences and panoramic views. I stayed there when I was in primary school and had fun jumping from one split level to another. There was also a sense of community as there is a communal garden deck where I played with my neighbours. Unfortunately, the iconic building has been sold en bloc and may be demolished.

For me to give Singapore an “A+” on its conservation efforts, I would love to see more open spaces, natural reserves and landmark buildings to be conserved.

Throughout your career, you have worked on numerous conservation projects. Which are the ones that you’re proudest of and why?

The project which I’m proudest of is the Central Fire Station project. It was my first conservation project; I designed the new dormitory wing and conserved the monument blocks. It was a humbling but fulfilling experience, as I felt satisfied to be able to be contribute to society and to the built environment. It was also great to see our design work recognised in numerous awards, news articles, and even a documentary.

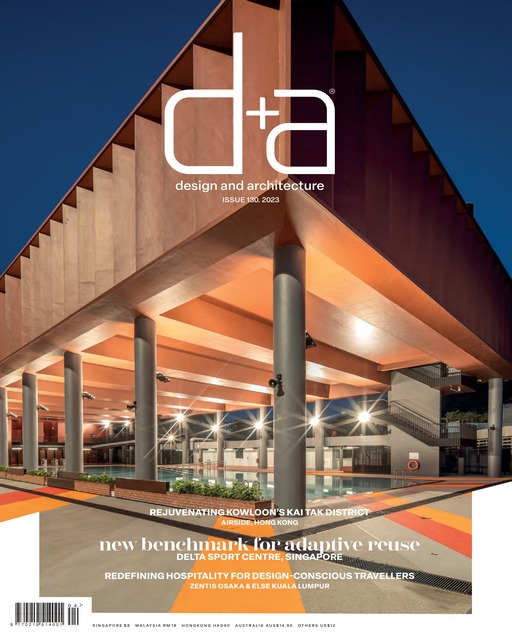

Central Fire Station

Central Fire Station

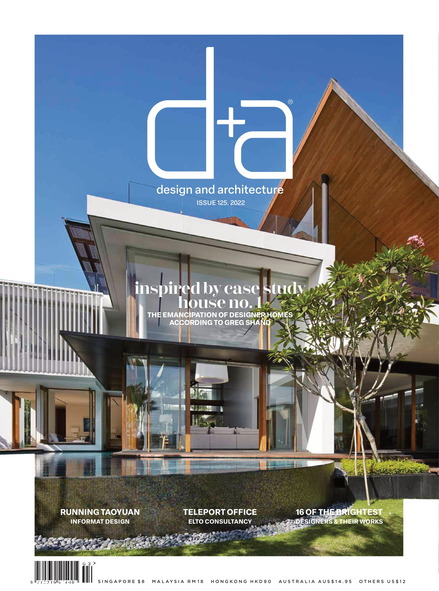

Another project which I am proud of is the National Gallery. This beautifully restored monument features tree-like structures that support a new filigree canopy roof, allowing us to create a chiaroscuro-like effect of light and shadows within the reconfigured interior spaces. In this way, we managed to craft exquisite spatial experiences for visitors, further elevating the experience for them.

National Gallery

National Gallery

Why do you keep doing (volunteering even) such projects? Why do you find them so compelling?

I take pride in the fact that architects can create spaces and objects of beauty that also make a positive difference to our societies and living environment. In addition to contributing to the important task of preserving our cultural heritage, this has also given me the opportunity to meet and interact with people from all walks of life, backgrounds and social classes. I have had interactions with Bangladeshi workers, Hokkien-speaking site foremen, foreign consultants and contractors, CEOs and academics, judges, and politicians.

What will you say is the biggest challenge you typically encounter in this area of architecture? How do you solve it?

The three “R” principles of conservation are maximum Retention, sensitive Restoration, and careful Repair.

Conservation work requires a significant amount of time to be invested into research. To properly carry out such projects – which means balancing the modern needs and purposes of the building, newer safety rules and regulations, as well as respecting the original intent and vision of the former designers and architects – we need to conduct proper research into the history of these buildings by examining archival drawings. In addition, investigations should be made into the cultural and social significance of such buildings, which may not always be neatly catalogued and archived in books and documents.

In the case of the Central Fire Station, I obtained copies of the original architectural drawings from National Archives, read up on more on its architectural style, the historical significance and events related to the building with SCDF giving inputs too. As many ad-hoc additions had been made over the years to the original building to increase space, we had to ascertain what had been part of the original structure, and what was most valuable to conserve. Site investigation is also an important part of the process; site visits and visual inspections were undertaken during the initial stages so as to gauge the condition of the building, followed by a detailed as-built drawing survey.

Another unique challenge in conservation work is the ideation and development of the best approaches and methods for the restoration and repair of building elements. Conservation work isn’t always part of a standard architectural curriculum, and many of the most interesting design elements of older buildings can be unique to this part of the world, which makes it even less likely that there would be established conservation and restoration methods to reference.

We also need to find the craftsmen who have the skills and materials with which to carry out restoration work. For example, in the case of the Central Fire Station, we found that there were missing bottle balusters within the balustrade. After considerable effort, similar balusters which could be used as replacements were finally found in Malaysia.

Tell us what your role is in the Singapore Memory Project. Why is this project important?

The Singapore Memory Project in an initiative that aims to document the history of Singapore as well as all its nooks and crannies, as experienced by both individuals and groups. Rather than the broad (and sometimes dry) overview that we get from textbooks and historical records of our country’s history, I believe this is an important project that helps to capture the nuances of our culture and heritage. As I had mentioned earlier, a country’s history is crucial in helping its people to develop a sense of belonging and community, and this project will help us to dive deeper into our shared heritage despite the relative youth of our country.

I have contributed context, background information, and behind-the-scenes insights of some of the iconic projects that I have worked on throughout my career, such as the Tuas Checkpoint, as well as restoration projects such as the Central Fire Station.

What message will you like to give to our urban planners on the matter of Singapore’s architecture conservation efforts?

I understand that in land-scarce Singapore, there is an extremely delicate balance between conserving our heritage architecture and ensuring that we have sufficient space to building for the future. Having said that, I believe that architecture is a critical part of a country’s culture and identity. I hope that our urban planners will continue to see the value in conserving prominent works by our own local architects, which will help local architectural talent flourish and grow the Singapore brand.

Who are some up-and-coming designers that you have your eye on?

I love what Serie Architects from the UK are doing, and find their work highly inspiring. CPG has been collaborating with them on the Singapore State Courts project, with them having taken the role of architectural design consultant for the project. I find their work to be refined and innovative, as well as sensitive to the setting and context of the site.

Share

Share