In HB Design’s newly launched monograph, accompanying the usual project descriptions and drawn, photographed, or rendered imagery are quotes – floating, unattributed quotes, such as the ones above – coming, presumably, from HB Design’s founder Hans Brouwer himself. The monograph is written by Paul McGillick and published by Tuttle Publishing.

That the architect’s voice is ever present through the pages is interesting. What is the point of the monograph, if not for a practice to express its ideas directly, and in its own terms?

A monographic volume can voice many things. It can present ideas, projects, or the preoccupations of a practice. It can be a manifesto that sets down philosophies and ethos. It can market and promote a practice’s best achievements. In effect, it is a useful tool for communication. And communication, as the reader of this monograph will learn, is an important and fundamental underpinning of HB Design.

After eight years of working at Foster & Partners, Hans Brouwer started HB Design in Hong Kong in 1995 with Anthony Wang, a friend and fellow graduate from the architecture school of University of Southern California. In the first chapter, Stepping Stones: Hong Kong 1995 - 1998, Paul McGillick writes, ‘While the background at Fosters clearly lent credibility, the real value of the time at Foster & Partners proved to be lessons learned from Sir Norman’s ability to communicate an approach, which distils a design concept into clearly formulated strategies the can be easily adhered to. Hans adopted three key principles: approach, process and buildability.'

While it is now working mostly on high-rise multi-residential and commercial developments, HB Design started, like most fledgling studios, with small interior projects. What does one make of this practice’s portfolio and successful expansion?

McGillick suggests reading it in terms of a process or processes. In the opening of the book, he makes a clever link, asking us to think of a ‘process’ as HB Design’s journey of growth and evolution, and on another level, in terms of how it is a highly process-oriented practice. On the latter, he writes, ‘What defines an architectural practice? The look of its work or its approach to the work and to their clients? Ideally, the two are indivisible. This is certainly the case with HB Design whose work is arguably recognisable not because it is a visual brand, but because its buildings seem somehow, through their expression, to tell the story of how they came to be the way they are, and of the process which has led to this beautiful and appropriate final product.’

Process and growth entail lessons. And the book does not shy away from sharing the setbacks and challenges faced. In fact, where it ventures to lay bare the reality of how architecture really happens is where the book really engages.

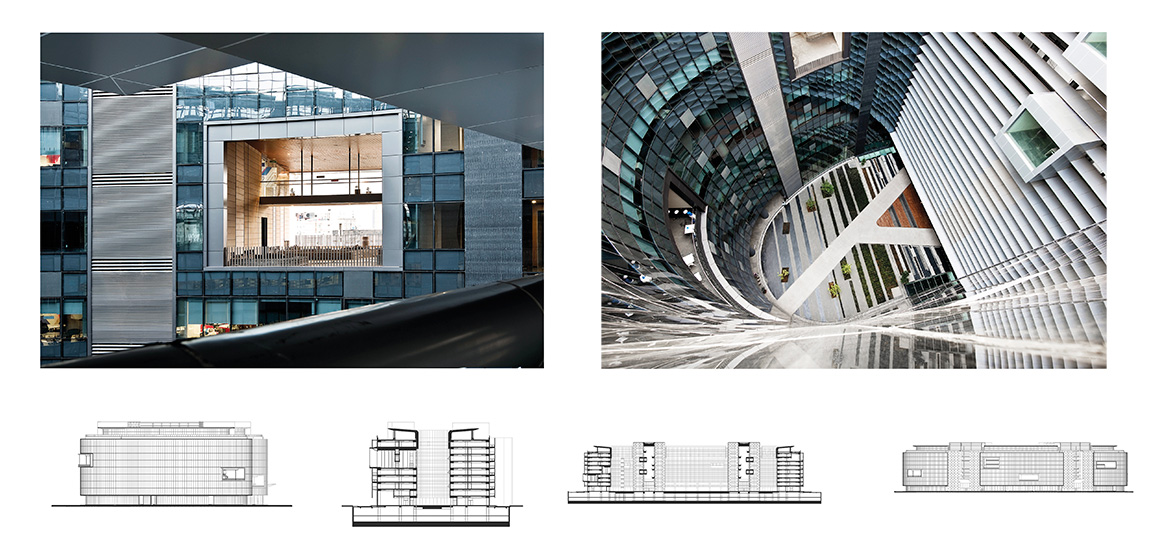

These come through some of McGilick’s descriptions of the projects. An example is of Studio City, a cineplex and performance venue in Wuhan, China, where fabrication challenges cropped up. The project had a curved walkway and an undulating metal wall made of customized steel fins. Designed uniquely, each of these metal fins had to be painstakingly hand-cut to match the curve of the walkway, perforated by hand drill, then finally lit by customized lighting. Of this episode McGilick writes, ‘This was “easy to design, but difficult to make” and succeeded by way of painstaking craftsmanship. Every fin was an early lesson [for HB Design] in the fact that a design is only as good as the architect’s ability to get it made.’

In Sotogrande, Spain, HB Design had a house that took five years and four contractors to build. ‘The problem,’ McGillick shares, ‘was building within a craft-based vernacular tradition, where the local contractors were used to building Spanish haciendas. The result was a disjunction between what was drawn and what got built. Regardless of the frustration, however, the project demonstrated the value of persistence and perseverance in achieving a successful outcome.’

Lessons relating to architectural practice can also be gleaned from Brouwer’s succinct, anecdotal quotes that float over specific projects. The architect’s summary of the Sotogrande house, for example, is: ‘This was about understanding how difficult it is to build well in a different culture.’ Others are more pointer-like: ‘You have to sell the entire building as a machine for working in and service small tenants with amenities they are not usually accustomed to.’ (Marvel Edge, page 120) ‘Look inside your own development, because the outside is all about the change and you don’t know what’s coming.’ (Gurgaon Gateway, page 176)

It is interesting that so many of Brouwer’s quotes are about lessons learnt. These become not just takeaways for the reader, they are significant, too, in how they make up that HB Design ‘process’ McGillick writes about in the opening of the book. These learnt lessons, teased out project by project, from perforated metal fins to high-rise units, are the true building blocks of the practice.

A print version of this article was originally published in d+a issue 90.

Share

Share