With its reputation of being the “Venice of the East”, given its extensive network of canals, there is undoubtedly much to love about Bangkok, the capital of Thailand.

This is what compelled Lim Hock Siang Tyler, a student at the National University of Singapore (NUS), to examine it at closer quarters and come up with a proposal on how it can embrace rising sea levels and turn this into an opportunity.

Dubbed “The Water Parliament – Bangkok City 2100”, it features three pieces of water infrastructure as urban redevelopment tools that also hope to revitalise traditional Thai water culture.

For his effort, he was recognised as the Gold Award Winner (Architecture Category) and Best Colour Award Winner at the Nippon Paint Asia Young Designer Awards 2021/2022 (Singapore).

Award winner Lim Hock Siang Tyler

Award winner Lim Hock Siang Tyler

“The concept stood out largely for the fact that it was a solution that is effected through government policy,” said Melvin Keng, Principal Architect of Kaizen Architecture and a judge of the Awards.

“It had the breadth and scope for it to evolve further. It also seemed like it could be applied tomorrow, making it the most plausible of the entries.

“The intelligent design solution to his forecasted problem seemed appropriate, considered and sensitive from a global and cultural perspective.”

We find out more about the project from Lim.

There are many cities in the world that face the threat of rising sea levels, including Singapore. Why did you focus your project on Bangkok?

I have been to Bangkok a few times for vacations with my family and friends. I love its nature. It is a magical city full of street life and water religious festivals. As water is peculiar to the Thai people, and looking at this most vulnerable city near the river edges, I decided to choose Bangkok because it is culturally rich and complex in its urbanism. The speculative premise of the project does not mean to promise a new city with absolute resiliency, but aims to bring awareness and explore how the adaptive use of water and the local community spirit of embracing this climate-induced changes can be valued as an opportunity to re-appropriate all these issues, eventually becoming a study model for other neighbouring cities that are at risk as well.

What challenges are the city face?

Built on soft clay and the over-extraction of groundwater, Bangkok has the dubious distinction of being one of the fastest sinking cities in the world – 10 times faster than the rising sea level. According to some estimates, parts of it are sinking by two centimetres annually, and if nothing is done, the whole city will be completely submerged in water by 2100.

Water, which used to be a sacred element that brings life to civilisations, is now threatening the survival of the Thai people. In earlier research I did during Semester 1 at NUS, traditional Thai water culture, various water management systems and the initial conceptual design of the future of water urbanism redevelopment had been examined to explore its role and meaning.

How did you present your entry?

As the project is speculative and conceptual, I illustrated it through a series of drawings that suggest a distance reminiscent of the Thai Mural Paintings that allow different scenes of life, stories and water infrastructure to co-exist in the same space with the same language. For instance, on board 3, you may notice that various narrative scenes are scattered around a larger environment, which tend to communicate a more global idea of the characteristics of this new Thai city in 2100. This showcases how the benevolent symbiotic urban growth is embedded in these three infrastructures, and how the Thai people are slowly adapting to their life in this new version of Bangkok.

Why do you call your project “The Water Parliament”?

Religious culture is considered an essential pillar of Thai tradition and rooted in its society. It is not only the major moral force of Thai families and communities, but also contributes to the individualistic and tolerant behaviour of people for many centuries. Today, Thai society portrays it in such a way where the Thai people are becoming an instinctive self as they are always subjected to higher power governance and dominance over their true selves. As such, The Water Parliament aims to take advantage of the environmental crisis of global sea-level rise to motivate the Thai people to participate and establish a parliament that they themselves can contribute to safeguard their property in the future.

Why situate The Water Parliament on Rattanakosin Island?

The main Chao Phraya River flows through Bangkok and stretches all from the way from Northern Thailand to the Gulf of Thailand in the South. Many canals have been displaced and make way for roads because of urbanisation. Due to the geological ground context where the Phra Nakhon District used to be the Rattanakosin Island during the Rattanakosin Kingdom, which was surrounded by water in all four directions, it is the district that has much more cultural meaning in reconnecting with water. It will also be the front leading isle that unfolds the three stages of intergenerational redevelopment as to how much the water will rise, and how the people can adapt their lives and facilitate the establishment of the Water Parliament over time.

Please explain how exactly it works.

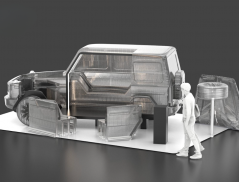

The Water Parliament works on three architectural strategies that allow the return of the ancient Rattanakosin Island in 2100. The three alternative water infrastructure are firstly, the Spiritual Embankment, which is a ring of defence around the ancient and historic monuments to keep them as they are when the sea level rises. It enhances the sacredness of these temples with aqua healing functions that allows visitors to be spiritually enlightened. Secondly, the Inhabitable Scaffold, which is a series of structures that are activated as inhabitable space when it floods. It facilitates a new business opportunity for the Thais, where the existing infrastructures near the monuments are adapted with new aquatic functions. Lastly, the Mangrove Lagoon, which is a line of coastal defences that sits at the edge of the old river system of Rattanakosin Island and uses mangrove to activate an aquaculture living and new form of eco-tourism in this island in Bangkok.

What are some examples of the functions of the Inhabitable Scaffold structures?

The Inhabitable Scaffold is driven by the concept of the “living” scaffold. This is heavily influenced by the scaffolding element of the existing infrastructure in Bangkok that ranges from illegal pop-up markets to street vendor carts and illegal veranda additions to permanent residences. As such, it allows most of the infrastructure outside the spiritual embankment to be redeveloped with new habitable spaces above. Using the idea of scaffolding allows the architecture to act as the vessel that allows the local inhabitants to input their culture through the integration of the water management literally, and indirectly, into urban planning architecturally and programmatically. The creative adaptation of a future living with scaffold infrastructures and water reveals the impressive spatial and temporal dynamics of Thai lifestyle, and also allows the city to continue being alive, crazy and unexpected. Additionally, it also helps to intensify some of the existing infrastructure, and frees up more water surfaces for activities that promote another form of eco-tourism experience in the new Bangkok.

Share

Share